Last month, I was enjoying the remarkably good crab cake and poached eggs at Just for You Café in San Francisco’s Dogpatch neighborhood, when I overheard a mentoring session taking place at the next table. I recognized the mentor as the famous, fifty-something ex-CEO of a household-brand Internet company; the mentee, I pieced together, was the twenty-something CEO of an app on my phone that had raised over $70 million in VC cash.

“My leadership team just gave me anonymous feedback,” Young CEO told Famous CEO. “One thing they said was that I’m not open to being questioned.”

“Are you?” Famous CEO asked.

“Yes!” Young CEO insisted. “After every conversation with my team and every all-hands, I always ask if there are any questions or concerns.”

“Let me guess,” Famous CEO said. “No one ever has any.”

“Right,” the mentee reflected. “Maybe I should hold office hours where people can raise concerns privately?”

“I used to do that,” Famous CEO said. “But here’s what happens. People come in, they talk to you about some important issue, and you give your thoughts. Then they go back to their teams and say, ‘The CEO said ___,’ and they lord your words over colleagues as a weapon. So I stopped doing that.”

“So what should I do?”

By this point, the mentee wasn’t the only one interested in the answer. In my work with CEOs and executive teams around strategic narrative, I often have a similar need—as anyone does who leads groups—to quickly take the pulse in the room.

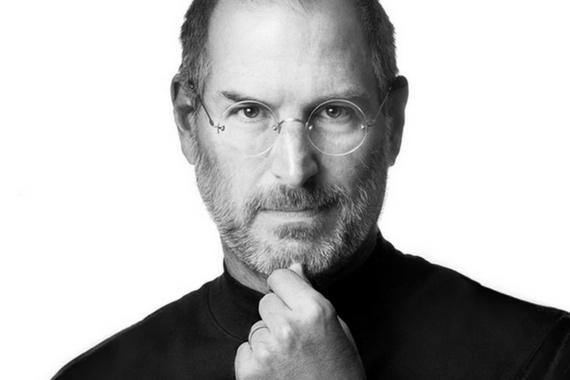

“Take notes on this,” Famous CEO said. “Because I’m going to tell you what Steve Jobs did, which was related to me by the late [Apple board member] Bill Campbell.”

I ordered another crab cake.

“In the early 2000s,” Famous CEO said, “Jobs was splitting his time between Apple and Pixar. He would spend most days at Apple, but then he would parachute into Pixar. He would have to figure out where his attention was needed really fast, so he would arrange sessions with all the different teams—the Cars team, the technology team, whatever—so there were a dozen or so people in each one. Then he would point to one person in each session and say:

Tell me what’s not working at Pixar.

Famous CEO continued: “That person might offer something like, ‘The design team isn’t open to new technology we’re building.’ Jobs would ask others if they agreed. He would then choose someone else and say:

Tell me what’s working at Pixar.

According to Famous CEO, Jobs would alternate between the two questions until he felt like he had a handle on what was going on.

Famous CEO said he ran sessions like these with his own teams every few months. He advised Young CEO to “never invite VPs” (i.e., team leaders) to the sessions, since subordinates might feel intimidated and share less freely. Instead, Famous CEO would commit, after collecting issues, to discussing them with the VP in charge, who would be responsible for following up.

A few days later, I led a workshop on strategic narrative design with about 40 CEOs, salespeople, and marketers. Just before it was over, instead of simply asking “Any questions?” as I normally did (which typically won me a roomful of silence), I called on a woman who, judging from her active participation in the class, seemed like she wouldn’t mind being singled out.

I asked her this question, inspired by that third-hand Jobs wisdom:

What is the thing I made most confusing today?

I worded it like this to position any confusion as my failing, not my audience’s inability to understand. I was also careful not to phrase it as a “yes-no” question (“Did I make anything confusing?”), which might have been more likely to elicit a polite “no.”

The woman said, “I’m still confused about how exactly the narrative elements fit together.” Of course, it was a question that I myself had been wrestling with for decades. My first reaction was to try to explain it to her in some different way, but instead I just said this:

I guess that’s because I’m still figuring it out, too.

The woman smiled, and her classmates seemed relieved. What I learned that day was how it puts my audiences at ease when I make a point to say how hard this stuff is (very), and how long it usually takes for most people to feel like they’ve landed on the right story (weeks, months, years).

Later, I called on another participant and asked: “What’s the thing you learned today that will most help you outside of this class?” As you can imagine, it was rewarding to hear about the positive impact I had made.

If you work with teams in any way, I recommend trying Jobs’s technique, my variation on it, or a variation of your own. And if you’re at Just For Your Cafe, I recommend the crab cakes. They really are very good, even without the complimentary side of Silicon Valley wisdom.

Originally posted on Medium by Andy Raskin