Fountain by Marcel Duchamp is considered a landmark creation of the 20th century.

It was produced in 1917, at a time when Duchamp was already renowned for his work. Seen as one of the pioneering artists of the last century, his art is spoken of in the same breath as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. It perhaps explains the shockwaves created by Fountain.

There are a few conflicting accounts of how Fountain came to be, but the most popular narrative is that Duchamp picked up a mass-produced porcelain urinal, labeled it “R.Mutt,” and then submitted it to the Society of Independent Artists to be displayed in New York.

A debate about whether or not it could be considered a piece of art ensued, and it ended with the society rejecting the piece, which led to its publication in The Blind Man magazine.

The reason for its fame is the conversation it started about what exactly art is. Is it something that should be objectively judged? Or does everybody get to decide their own definition?

The art world still grapples with these questions. That said, this isn’t just about art. Hidden in this debate is something fundamental about human nature. It’s something we all experience in other contexts of our lives, too. Most notably when we communicate with each other.

The ability to communicate effectively, whether it be in your personal or professional life, is one of the most crucial skills one can have. That’s where every valuable relationship begins.

As we’ll see, due to reasons similar to those responsible for Fountain’s fame, however, that’s often difficult. That said, if you understand the forces at play, you can refine the ability.

Being a good communicator is more than just words. It requires deep understanding. Here are three important ideas to understand.

1. Know the Paradox of Communication

The heart of the argument about whether or not art is something that can be judged by a universal metric isn’t really about objectivity. It’s about the role of subjective experience.

Everybody has a unique genetic predisposition, and we’re all a product of our different experiences that shape our preferences, tastes, and feelings about our surroundings.

What feels and looks good to one person could be utterly repulsive and off-putting to someone else. The question in art isn’t whether or not everybody has a subjective view. We know that everybody does, but it’s whether or not that should matter when it comes to judgment.

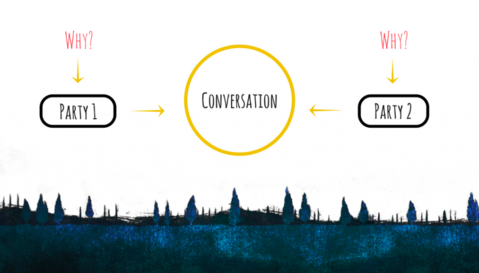

Now, let’s take this and apply it to a broader communication problem. A debate on a topic between two people who are on the opposing end of the political spectrum of belief.

If you take a second to observe most such debates, you’ll realize that the two people involved will never see eye-to-eye. The reason is simple. On the surface, they may be arguing about something like healthcare or taxes, but that’s not where the actual conversation is occurring.

The reason they can’t see eye-to-eye is that before they even walk into the debate, they both begin with underlying subjective assumptions about what is right and what is wrong, and it doesn’t really matter what the issue on hand is because they’re not speaking objectively.

Each party thinks that their subjective belief (and it’s definitely subjective) that their position is right is the objective truth, and they argue as such. That’s the paradox of communication.

We take our subjective experience, and we torture it to fit a reality that aligns with our preferences rather than trying to understand what’s happening from every point of view.

2. Recognize the Incentives of a Conversation

Knowing this paradox of communication can go a long way in helping you establish some boundaries when interacting with people close to you, but it doesn’t always work.

People are often attached to their ideas and beliefs, and it’s hard to get them to let go of them. Similarly, you likely have your own viewpoints which you’re not willing to compromise on, and it’s not always effective to go in with the mindset that you’re going to see eye-to-eye.

In such situations, the best way to maximize the success of an interaction comes down to understanding the incentives that the person you’re with has for being in the conversation.

Even if you won’t or can’t see eye-to-eye, you can still get the most out of the interaction if you know what they want, and you can do this without compromising on what you want. Sometimes, the best solution isn’t to drill into the truth, but it’s to resolve a problem.

In some conversations, the person is looking for something like an apology (with a spouse after a fight, for example), and in others, it will be something that demands a little more of you, and that may even conflict with your interests (a mediocre employee requesting a raise).

Say that you misread the situation with your spouse after a fight and presume that the next conversation will be a continuation of that fight, even though your spouse is indicating that what they’re looking for is a simple “Sorry, I’ll be better next time.” The chances are that you’re going to end up digging a deeper hole into a situation that doesn’t demand it.

Similarly, if you know that the employee feels like they deserve a raise, even though they haven’t quite earned it, rather than arguing with them about it, it’s smarter to establish objective metrics for them to pursue over a period of time than it is to shut them down.

It saves you from demoralizing them, and it keeps their incentive alive. If they do meet your objective criteria, then presumably they’ve added enough value to actually deserve a raise.

When you seek to understand the incentives involved in a conversation, you can get out of it what you want without the struggle of battling your subjective viewpoint with someone else’s.

3. Learn to Treat People Like Stories

At the end of the day, good communication comes down to empathy. It’s just about putting yourself in somebody else’s shoes before seeking to establish any sort of alignment.

Outside of maybe professional critics, the reason somebody likes a particular piece of art is due to the cumulation of their own experience and how that fits into the narrative of the piece that they’re observing. It’s about what it makes them, specifically, think and feel.

Similarly, the reason someone holds a certain viewpoint is due to the connection that their viewpoint has to their life story, and the subjective experiences that make up that story.

One of the most effective things you can do before you go into an interaction or before you engage in an argument with someone is to ask yourself, “What is it that makes this person who they are, and how may the impact of their experiences dictate their outlook?”

Everyone has their own story of who they are and why they do what they do. Many people fall into the trap of looking too closely at the surface-level discussion, and they fail to recognize the underlying forces that are responsible for directing that discussion.

If you treat people like the stories that shape their outlook, you’ll be in a far better position to either win them over or better understand their position. Not only is empathy a virtue, but it’s also the best way to improve your communication skills.

All You Need to Know

Humans are a networked species, and communication is the lifeblood of that network. Knowing how to excel in your interactions with other people is an indispensable skill.

Duchamp’s Fountain may be most pertinent to discussions about art, but the broader insight that comes from the questions it raises tells us a lot about human nature, too. Many of the conflicts that occur between different people find their roots in the subjectivity of perspective.

How effectively you communicate influences everything from the quality of your intimate relationships to your ability to convince other people to align their actions with your goals.

If you can master the fundamentals of human interactions, there is almost nothing you can’t do.